An excerpt from

A Vision Realized: The story of Ludwig Cancer Research

You probably know Ludwig Cancer Research is named after a billionaire. Many of you might even recall that the billionaire in question, Daniel Keith Ludwig, made his fortune in shipping and, perhaps, that he is credited with inventing the modern supertanker. But we suspect very few, even in the extended Ludwig Cancer Research community, know much more than that about the man, such as where he came from, what he was said to be like or how he built the sprawling conglomerate that made him one of the richest men in the world. This is not your fault. Ludwig cherished his privacy and worked hard to protect it—even from the prying gaze of posterity.

If you’re curious to learn more about the man, read on. The article that follows is carved out of a book on the history of Ludwig Cancer Research prepared by the Communications department. That history owes its creation to chairman-emeritus of the Ludwig Institute’s Board of Directors John Notter, who suggested that somebody write the story of the Institute, which he helped conceptualize and establish and whose founding Board he chaired until 1980. He returned to the Board in 2009 and took the chair once again the following year. After 14 years at the post, John was replaced in July by the Institute’s retiring CEO and President Ed McDermott, though he remains on the Board.

We thank them both for their support and contributions to the Ludwig Institute history, from which we excerpted the following biography.

Daniel Keith Ludwig was born on June 24, 1897, in South Haven, a small port town on the Lake Michigan shore, where a pier built by his grandfather bore the family name.

Shipping was in his blood. As, clearly, was business. He told a Fortune magazine reporter in 1957 in an exceedingly rare, sanctioned profile that when he was just nine years old, he pulled together $75 to buy a sunken, 26-foot boat and toiled through the winter to fix her up. He then hired a crew and chartered her out the next summer for twice as much as he’d paid for her, all while earning extra on the side shining shoes and selling popcorn.

When the young Ludwig’s parents divorced six years later, he dropped out of school and followed his father, a real estate agent, to Port Arthur, Texas, where he endured a singularly lonely childhood. Ludwig eventually found work selling supplies to ships anchored at the local port while attending night school to pick up the math he needed for marine engineering. He then moved back to Michigan and completed his training working at 20 cents an hour for the manufacturer Fairbanks, Morse and Co., which subsequently hired him and sent him off to the Pacific Northwest and Alaska to install ship engines.

Ever the entrepreneur, Ludwig freelanced his services in his spare time and soon decided he preferred being his own boss. With $5,000 borrowed on his father’s signature, the 19-year-old Ludwig bought an aged side-wheel excursion steamer named Idlewylde, paid back the loan by selling off its machinery and boilers, and converted the ship into a barge. The conversion, which entailed extensive welding of bulkheads in the cargo spaces using a simple but effective method, left a lasting impression on Ludwig and later influenced his pioneering construction of supertankers. Buying some wooden boats to assemble a ramshackle fleet, Ludwig began hauling liquid molasses up the Hudson River to distilleries in Canada during World War I.

That business was, however, short-lived. Ludwig sold his barges to his erstwhile client and stayed barely a step ahead of bankruptcy using his decrepit tugs for general hauling during an ensuing downturn in the shipping business. He noticed around this time, however, that transporting oil was about four times as profitable as hauling molasses. So he chartered out a small, nearly finished tanker from the United States Shipping Board, sold his tugs to complete its construction and began oil deliveries for a Massachusetts refinery.

In 1923, he bought an antique, partly sail-driven tanker, the Wico, for $25,000 from a scrap metal dealer named Boston Metals Co., claiming outright ownership of an ocean-going vessel for the first time and starting a lasting business relationship with the dealer. But a partner he enlisted in that business soon elbowed him out. Undeterred, Ludwig established a company named American Tankers Corp. with new partners a couple of years later, this time buying a tanker named the Phoenix from the United States Shipping Board.

Seeking to expand his business, Ludwig next returned to New York and bought a coal-hauling vessel named the Ulysses, which he converted into a 14,000-dead-weight ton (dwt) tanker—enormous by the standards of the day (dwt refers to the total weight a ship can carry, including cargo, fuel, ballast, passengers and everything else onboard). That move nearly bankrupted Ludwig when delays in the collier’s conversion led to the loss of its charter. But the failure would ultimately spark a rally in Ludwig’s fortunes when he managed, in 1937, to offload his white elephant to a whaling concern for four times its value as a tanker.

The proceeds pulled him out of debt and financed the hiring of his first full staff. Around the same time, Ludwig also obtained from New York’s Chemical Bank a loan he considered the most consequential of his career, using it to buy several government cargo vessels, which he converted into tankers. By 1942, Ludwig had his own shipyard for building and converting ships into tankers—Welding Shipyards, the first of two he’d operate in Virginia.

He was innovating on the financial front as well. In 1938 Ludwig pioneered a mechanism for financing his growing fleet that would later become standard in the industry. He would charter a tanker to an oil company for a certain number of years and borrow from a bank for the same term to finance the construction of new vessels or support other investments. The oil firm would then pay the monthly charter fees to the bank, which would take its cut and transfer the rest to Ludwig. Comprehensive insurance coverage of the ship would protect the bank. Ludwig, for his part, could borrow on existing vessels, sure that the loan would be repaid; and the new vessels, which he owned entirely, could serve as additional collateral.

By the late 1940s, under the skeptical gaze of his competitors, Ludwig was building larger and larger tankers on the calculation that they’d be more profitable because operating costs do not rise in direct proportion to ship size. His hunch proved correct and, encouraged by the results, he signed a deal with the Japanese government in 1951 to lease the Kure shipyard, where the graving docks and other factors greatly eased the application of his many innovations in supertanker construction. His tankers grew from the neighborhood of 23,000 dwt, considered gargantuan when introduced in the 1940s, to a staggering 326,000 dwt a couple of decades later. By the late 1960s Ludwig had six such “Bantry Bay Class” Goliaths plying the oceans, part of a fleet that grew to number more than 60 ocean-going ships at the height of his career.

Ludwig’s engineering chops were a core asset of his businesses. Having developed pioneering welding techniques at his Virginia shipyards, he continued innovating at Kure, where his use of prefabrication and sectional pre-assembly streamlined the production of his supertankers. The components and designs of his ships were largely interchangeable, ensuring further efficiency in not only their construction and maintenance but their operation as well: crews could be moved around as needed from ship to ship and feel at home wherever they were dropped.

Like the man himself, the tankers were notably frugal. They lacked basic comforts such as air conditioning, let alone frills like swimming pools, luxurious captain’s quarters or “owner’s cabins.” Yet, as characteristically, Ludwig was happy to pour large sums into structural and mechanical components that would improve their profitability. He similarly spared no expense in hiring only the best officers to run them. As the American Society of Mechanical Engineers noted in posthumously awarding Ludwig the Elmer A. Sperry Award for Advancing the Art of Transportation in 1992, “His ships are known the world over as lean and austere in appearance, but they are recognized as exceptionally durable and reliable in machinery, equipment and basic structure.” His design innovations in shipbuilding, it additionally noted, extended well beyond the supertanker to encompass dredges and bulk carriers and even a floating power plant that could be hauled across oceans and dropped off at remote locations.

On the foundations of this fleet, Ludwig built a commercial empire. His investments certainly overlapped at times: If his ships needed coverage, he established an insurance company; if the shipyards needed steel, his cargo ships, chartered out to U.S. Steel, hauled iron ore from a Venezuelan mine to smelters in the U.S. Inventive as ever, Ludwig personally designed gigantic bulk carriers for that purpose and had them ferry the ore over a channel deepened by a dredge of his invention.

By 1963, his stack of holding companies—of which he was sole owner—had interests in an oil refinery and an orange grove in Panama; a potash mine in Ethiopia; iron, coal and oil interests in Australia; an international chain of luxury hotels; an oil refinery in Germany; the Kure shipyard and a cargo transfer complex in Japan; a 650,000 acre cattle ranch in Venezuela; interests in oil companies in Canada and California, a state where he also controlled a clutch of savings and loan companies; the world’s largest manufacturer of salt by solar evaporation—Exportadora de Sal—in Mexico, whose salt harvesting and other machinery he developed and built, and that he serviced with self-discharging carriers of his design that docked at a deep-sea port he constructed at Cedros Island; and, of course, a fleet of 22 bulk carriers and 28 supertankers that was expanding at a steady clip.

Ludwig left his mark in residential real estate as well—most notably Westlake Village, which he built on a storied 11,780-acre ranch he bought in 1963 for $32 million (the equivalent of $328 million today) just 40 miles outside of Los Angeles. What Ludwig saw at the time, and others did not, was that it was only a matter of time before a highway to the nearby city ran past the ranch. With that, the natural beauty of the land—hundreds of Hollywood movies had been filmed there—and its proximity to L.A., any development at the location was likely to be successful, if done correctly. To ensure it was, Ludwig established a subsidiary of his American-Hawaiian Steamship Co. (AHS), named American-Hawaiian Land Co., to manage its development. Notter, who was chairman of the AHS board and now chief of its subsidiary, retained a civil engineering firm to design not just a housing development but an extensively planned city.

The effort involved the integrated contributions of hundreds of experts in dozens of specialties—from schools to healthcare to hydrology to cemeteries to land use—working in concert to create a master plan for a city of tens of thousands, complete with homes, parks, schools, greenbelts, lakes and marinas, shops and industrial zones. The project involved the construction of a $3.5 million lake, stocked with catfish and bass, boasting eight elegantly designed miles of shoreline. Westlake Village was a spectacular success and is still considered among the best planned cities in the country.

By the early 1970s, Ludwig’s net worth was estimated to be in the billions. He had added oilfields in Indonesia, real estate in Australia, skyscrapers and other properties in the U.S., iron and kaolin mines in Brazil and a whole lot more to his skein of enterprises.

Yet Ludwig’s confidence in his own vision could be blinding and would lead him, in the late stages of his career, into a mire of his own making. Anticipating, correctly, an impending fiber shortage, Ludwig bought a tract of land more than twice the size of Delaware in the Brazilian Amazon for $3 million in 1967. His plan, named the Jari project, was to raze most of the rainforest on his property and replace it with the fast-growing Burmese gmelina tree, supplementing that fiber-making enterprise with mining and ranching operations. The project was highly controversial and became something of a political lightning rod in and even outside Brazil. Despite ample warning to drop the project, Ludwig would persist until 1982 and leave only after the political situation in Brazil became untenable. By some estimates, he lost nearly $1 billion, in 1981 dollars, in the enterprise.

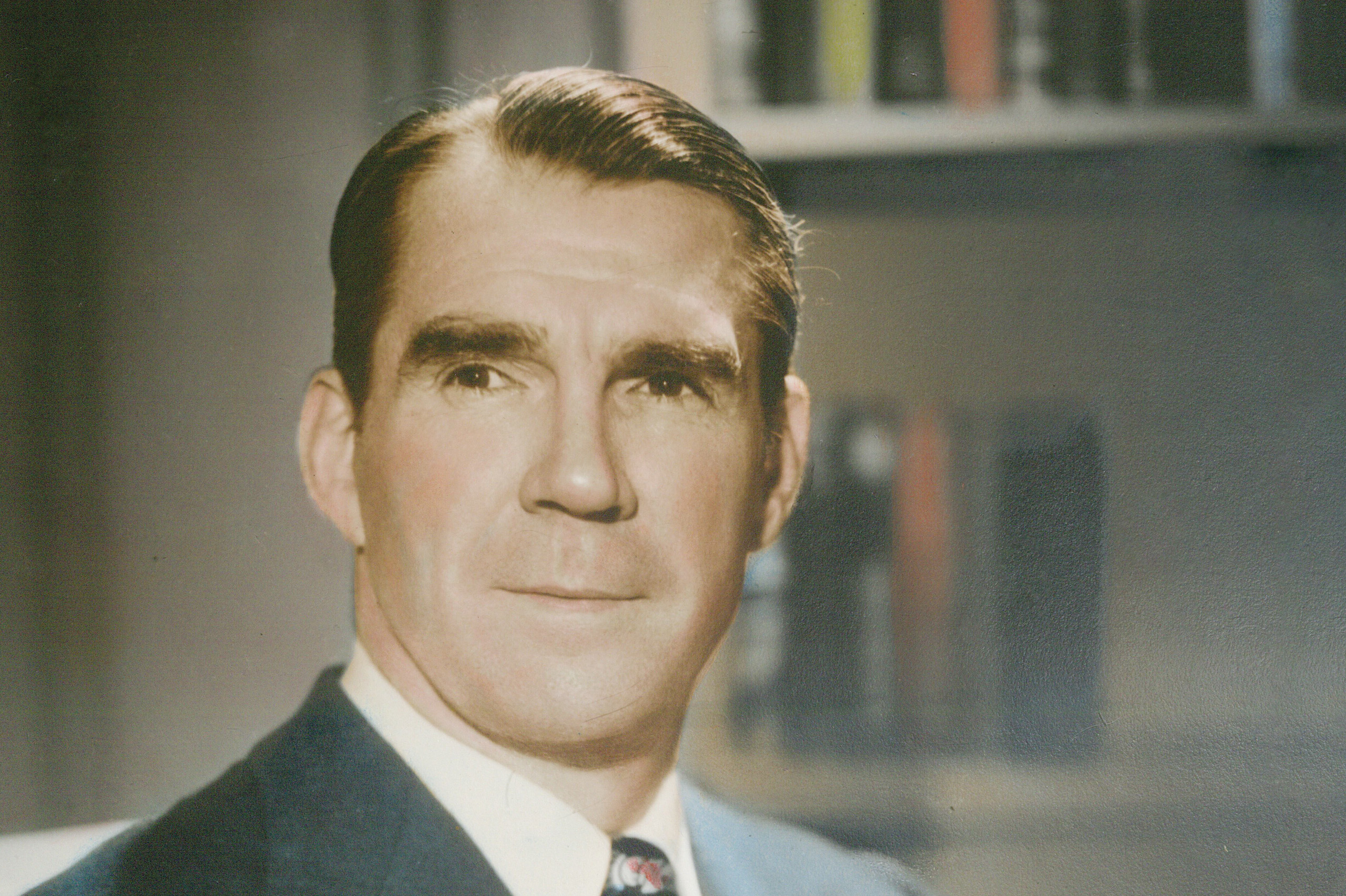

Still, even with the press generated by the Jari project, hardly anyone outside the shipping industry knew who Ludwig was. This was entirely by design: laconic and intensely private, Ludwig detested publicity of all kinds. If frequently blunt, cantankerous and openly bored by small talk, he was also very loyal to the few friends he had, who were mainly business partners and lawyers he’d known for ages. His other friends included the actor Clark Gable, who Ludwig revered, and Richard Nixon, who was a guest at his home before he was elected president. A conservative in the old sense of the word, Ludwig held Ronald Reagan in high regard, prominently displaying a picture of himself and the future president in his Manhattan penthouse. He was said to be devoted to his wife, Gertrude Virginia Ludwig, whom he had married in 1937, just a couple of months after divorcing his first wife, from whom he seems to have been estranged soon after their marriage began in 1928.

In public, and especially in his old age, the titan kept a low profile—though it would be an exaggeration to say he was a recluse. He flew economy, used public transportation, walked to work and otherwise played the part of an ordinary if somewhat enigmatic old man with determined fidelity. He went to great lengths to keep his name out of the press, even taking his executives to task when it cropped up in print unexpectedly. And though, being one of the richest men in the world, he could have done almost anything he wanted, he confessed he had no hobbies or even interests beyond business.

Except, evidently, an abiding fascination with the conquest of cancer.